The following article was printed in the New Zealand Herald as rebuttle to the previous article calling for Top Gear to be Junked. Ben Fenton from the Telegraph Group obviously disagrees.

Two words are guaranteed more than any others to provoke me. The first is "provocative", when used in a way that ignores the dictionary definition of the verb "to provoke": to annoy or infuriate someone, especially deliberately; to incite or goad.

The second is "healthensafety", which began its wretched existence as three words, but has become one. Between them, they encapsulate some of the most tiresome aspects of British life.

Hugely popular and boorish television programmes such as Big Brother and I'm a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here! are justified by their producers as "provocative".

In a genuine world, it would be enough to justify Big Brother because it supplies the second aspect of Juvenal's recipe for controlling the mob - bread and circuses. But that idea might be too provocative.

"Healthensafety" was invented in the 1960s by civil servants to create jobs for their own children. Its primary function is to stop everyone who wants to do more with their lives than eat bread and watch circuses, from having any fun.

The BBC often has to defend its motoring programme Top Gear from criticism of its presenters' sexist or xenophobic comments, or their glorification of environmentally unfriendly driving.

It usually claims that the programme is meant to be "provocative".

Perhaps it means it in the dictionary sense, but I doubt it. Knowing the BBC, it probably means that Top Gear is naughty, but attracts huge audiences.

Five hundred complaints in six months about a programme that reaches five million people a week is simple maths for 21st-century broadcasters.

Last week, Richard Hammond, one of the trio of politically incorrect Top Gear presenters, lay in a neurological ward in Leeds after flipping a drag-racing car while driving at close to the British land speed record of 300.3 miles an hour (482.3 km/h).

His comrades, James May and Jeremy Clarkson, spent time at his bedside, but they and the huge staff that produces the programme must have been conscious that "healthensafety" is now as great a threat to the future of Top Gear as the laws of physics were to Hammond's life.

A BBC spokesman talked of a "healthensafety investigation" during the day and to many fans of the programme, it sounded like a herald announcing the arrival of the Spanish Inquisition.

By the weekend, more than 1000 people had sent Hammond their good wishes on the BBC's website. It was a testament to the popularity of the man, but also of the programme.

In our risk-averse and emasculated society, watching people fool around at high speed in cars answers a basic human need, even if only vicariously.

Children, mine included, love Top Gear and that is not surprising, because their lives are particularly restricted by the undiscriminating edicts of the riskaverse.

And, of course, Top Gear is a very childish programme. The humour is childish - using a medieval catapult to throw a particularly awful Nissan through the air, or dropping a caravan from a height is slapstick, but it delights my 11-year-old and me equally.

The jokes meander towards puerile xenophobia -- Clarkson said the BMW produced Mini Cooper would be more quintessentially German if its satellite navigation system was set to invade Poland.

The ritual humiliation of the weak is cruelly childish. Caravanners, cyclists, environmentalists and the dull are Top Gear's favourite targets.

Inventing ways of destroying caravans occupies much of the producers' time, and ridiculing safe drivers or "green" roadusers provides an easy laugh.

Yet its psychological geometry leads to a single point - driving is easily transformed into a mundane activity, but it is also one of the few affordable ways human beings can defy our natural limitations. Or, in other words, have fun.

Fun should be safe, but only if you are supervising somebody else or doing something that affects other people's security and property. Otherwise, fun should just be fun.

Personal risk should be a matter solely between a person and his or her insurance company.

That is the essence of Top Gear. Humans have climbed all the mountains and travelled up all the rivers that the planet has.

We haven't explored all the oceans, but there is a limit to the interest you can take in translucent fish. Few of us can visit Everest or the Amazon basin, still fewer can pilot a bathysphere, but we can watch someone else do it.

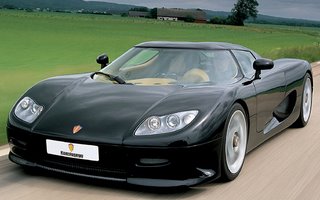

Few of us can afford a Bugatti Veyron, but we might be able to imagine what it's like to sit behind the wheel of one, and we want to see it driven fast, because that is what it was built for.

Hammond, Clarkson and May are paid to have fun on our behalf and make us laugh while they do so. They do a very good job of it. Of course, they aren't always justified in doing what they do.

Their antics with an antique Jaguar C-type were condemned by my colleagues, and could have led to a duel at dawn if "healthensafety" had permitted two sets of motoring journalists to fling spark plugs at each other from 20 paces.

Overall, Top Gear simply celebrates transport as risk-taking rather than travel.

Last year, the lobby group Transport 2000 berated Clarkson and the others for favouring performance over efficiency and conservation. They proposed replacing Top Gear with something more moderate and green.

The BBC must resist any calls to put Hammond and his friends in any other gear than top, or apply any brakes to their adventures, because, if it can tolerate them being "provocative", or even provocative, then it can certainly let them continue in the fast lane, waving two fingers out of the window in the direction of "healthensafety".

No comments:

Post a Comment